How are the members of the G20 rich nations club performing in their efforts to meet the challenge of climate change? A new report prepared for a recent G20 summit says: “Not enough. Must do better.” It urges them to drastically improve energy intensity and phase out support for fossil fuels.

Amid the plaudits for China and the US ratifying the Paris Agreement is the knowledge that the world’s greenhouse gas emissions are still rising, and that the G20 is responsible for three quarters of these emissions.

A new report from Climate Transparency, a conglomeration of global NGOs dedicated to urging climate action, analyses the relative performance and investor-readiness of the world’s richest economies in moving to a low-carbon state.

It challenges them all to submit plans by 2018 detailing how they will decarbonise by the middle of this century and to commit to basing their infrastructure investment on keeping the global average temperature increase to well below 2°C, and to encouraging green investment.

Climate Transparency says that to achieve these aims a realistic price for carbon is vital, whether achieved through a tax, levy or emissions trading.

Absolute emissions by G20 countries must be drastically reduced in the near future; between 1990 and 2013 their energy-related CO2 emissions actually increased by a depressing 56 per cent.

|

Per capita emissions in the G20 nations. |

If global emissions are averaged on a per person basis, then in 2013 everyone in the world was responsible for 5.7 tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions a year.

The report says that to keep global temperature increase below 2°C this must be reduced to around two tonnes per person – in other words we must each have our emissions cut by two thirds.

The G20 scorecard

So, how do the individual members of the G20 size up in the race to reduce emissions? Here are the headline results:- All of them, except Brazil and Russia, are reducing the energy intensity of their economies.

- The UK has the lowest energy intensity, mainly because its economy is predicated largely on its services and financial sectors. Countries with large manufacturing sectors face greater challenges.

- Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia and the United States have the highest per capita energy-related carbon dioxide emissions.

- India and Indonesia have the lowest emissions per person, but Brazil’s and India’s are rising as they develop.

- All G20 countries except Argentina and Saudi Arabia have implemented policies to encourage energy efficiency in buildings and emission performance standards for vehicles.

- Only half of the G20 members have published plans for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, or expect to do so.

- Only the UK and Japan have exceeded the climate policy framework specifications for boosting performance.

- G20 governments collectively provided almost AU$92 billion in subsidies for fossil fuel production between 2013 and 2014. Of these, Russia subsidised its sector by a whopping $31 billion, the United States over $26 billion and Australia and Brazil $5.8 billion each.

The urgent need to cut fossil fuel subsidies

In 2009 G20 leaders promised to phase out these fossil fuel subsidies.Other NGOs put the figure for the G20’s subsidising of fossil fuels even higher. The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and Oil Change International say it is more like AU$583 billion a year.

Insurance companies worth over $1.2 trillion last week demanded that G20 governments commit to phasing out these subsidies by 2020. Aviva, Aegon NV and MS Amlin, along with the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries and Open Energi, all signed a statement to this effect.

One of the main obstacles for decarbonisation continues to be plans for new coal-fired power plants. Amongst the most worrying of these is Australia’s commitment to supporting these in the Far East with dramatic expansions of coal mining that threaten the Great Barrier Reef.

|

| G20 members’ support for coal. |

South Africa and China both rely almost 70 per cent on coal for their energy, but others are also guilty: Australia (at 37 per cent), Germany (at 26 per cent) and Japan (at 25 per cent).

If all the plans for new coal-fired power stations were implemented it would double the world’s existing capacity. This must be halted, says Carbon Transparency.

|

| G20 members’ support for renewable energy. |

Renewable energy on the other hand is a big success story in the G20. It increased by 18 per cent since 2008. Leading countries are: Brazil, Canada, Italy, India, South Africa, Turkey and the EU.

Guess in which G20 country renewable energy actually declined between 2008 and 2013? Well, it was Mexico. That is expected to change.

How investor-ready is the G20?

|

| The G20 countries score table for investor-readiness. |

So if the G20 is to shift from brown to green energy, then countries must become what is termed “investor-ready” for renewables and energy efficiency.

The Carbon Transparency report ranks countries on their investment-readiness. It finds China, France, Germany, India, the UK and the United States are already attractive to investors.

What counts in this respect is the coherence and reliability of energy and climate policy, which provides confidence to investors. For example, Germany is now seen as not quite as attractive as it was because it has introduced caps on subsidies for renewable energy.

The least investor-ready countries are Russia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Both offer little support for renewables and their national grids are not yet adapted to their integration. Since President Erdogan took power in Turkey, energy policy has favoured coal at the expense of renewables.

Under global climate agreements eight developed countries in the G20 are supposed to offer cash to other countries to develop their low carbon economies.

But this is not yet sufficient. In 2013-14, France, Germany, Japan, the UK and the US each provided between US$1.2-8.4 billion.

Although that sounds like a lot of money, in relation to GDP it is low. If you look at it from this angle, Japan (at 0.18 per cent) and France (at 0.12 per cent) have the highest ratio of providing international climate finance per head of population.

At the bottom of this table are Canada (0.0008 per cent), Australia (0.001 per cent) and Italy (0.0003 per cent).

Reducing carbon intensity

If we are to move to a low or zero carbon economy and improve the living standard of everybody on the planet then carbon intensity must reduce equally everywhere. This means producing more with less polluting energy.Carbon intensity varies wildly amongst the members of the G20. The least efficient is South Africa (at 925 gCO2 /KWh). It is followed by India, Australia and Indonesia, who all have electricity emissions intensities of over 800 gCO2 /KWh.

|

| G20 members’ carbon intensity compared. |

None of them perform so well when compared with Norway, which beats the world with just 8g CO2/kWh.

So what are they all doing about it?

For the Paris climate summit all G20 states submitted Intended Nationally Determined Contributions. These were supposed to show what they were going to do about climate change.However the emissions reductions stated in these documents only cover 15 per cent of those needed to reach under 2°C. To achieve that, the G20 members need to ramp their climate action ambition up to 2030 by six times.

Among the tools needed, besides climate finance, is carbon pricing. Common pricing makes it more expensive to pollute than not to pollute when producing energy.

Australia’s emissions trading system introduced this year is criticised because its baselines are so high that they don’t not require any emissions cuts. And it repealed its comprehensive carbon price mechanism in 2014.

Throughout the world, carbon prices vary significantly from below one US dollar a tonne of carbon dioxide to US$130 a tonne, with the majority (85 per cent) priced at less than US$10 per tonne. Ideally, the world needs to move to a harmonised system of carbon pricing.

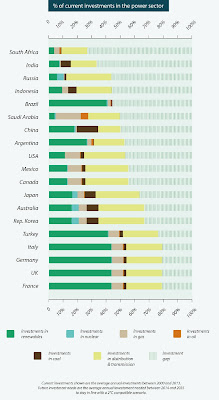

Looking forward, here is a table of how the countries compare in their planned investments in energy:

|

| G20 planned investments in energy |

Conclusion: the transition is happening but the speed is yet too slow.

David Thorpe is the author of:

- Best Practices and Case Studies for Industrial Energy Efficiency Improvement (with Oung, K. and Fawkes, S. UNEP, 2016)

- A London Conversation: Business Briefing on Green Bonds (The Fifth Estate, 2015)

- The One Planet Life (Introduction: Jane Davidson. Routledge, 2015)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Energy Management in Buildings (Earthscan, 2013)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Energy Management in Industry (Earthscan, 2013)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Solar Technology (Earthscan, 2011)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Sustainable Home Refurbishment (Earthscan, 2010)

No comments:

Post a Comment