|

| The geography of fuel poverty: where you live determines how high your fuel bill is. |

Despite London’s world-class status, exorbitant property values and all the foreign cash flowing into its property market, over a third of its non-domestic buildings and a quarter of its homes have the lowest energy efficiency ratings.

[NB: This article first appeared on the Fifth Estate website on 3 August]

The revelation comes from a survey of Energy Performance Certificates, the official way of measuring the energy efficiency of buildings in the UK, that have been issued in the last six years, undertaken by the Association for the Conservation of Energy.

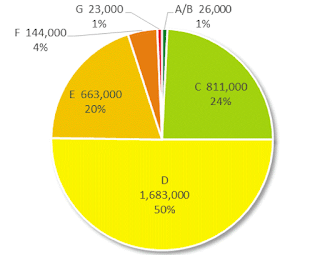

The proportion of homes meeting the different levels of energy performance in London.

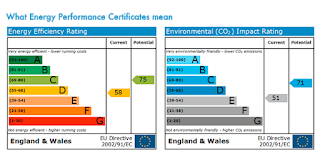

Understanding Energy Performance Certificates

By studying the certificates ACE found that 37 per cent of non-domestic buildings had been rated E or lower since 2009 and only around a third (34 per cent) had performance ratings of C or higher.

In the housing sector, 830,000 were awarded the lowest energy efficiency ratings of E, F or G, with 18,000 homes in the bottom two extremely poor categories.

In the same period, foreign investors have apparently bought £100 billion (AU$175.2b) of London property and London has become the most expensive capital in the world for employers to house their staff.

But none of this cash has “trickled down” to help improve the building stock used by the majority of London’s inhabitants.

Pedro Guertler, the research director at ACE responsible for the study, said: “We were shocked to discover that a quarter of London’s homes and 37 per cent of its workplaces have the very worst energy ratings and therefore waste a large proportion of their energy.

“Millions of the capital’s homes and businesses still stand to gain from energy efficiency upgrades.”

He gave a striking example: “If shops cut energy costs by 20 per cent, it would be the equivalent of a five per cent increase in sales.”

Commercial and industrial buildings make up about a quarter of London’s building space but consume almost half of its energy, resulting in them emitting about 42 per cent of the city’s carbon emissions.

The £7.9 billion fuel bill

London’s homes and workplaces spend upwards of £7.9 billion (AU$13.8b) on energy bills every year, £4 billion (AU$7b) of which is paid by workplaces. This is money that leaves London’s economy. ACE makes the point that, by contrast, improving efficiency and cutting energy costs actually represents an investment in the capital’s economy, as well as improving its energy productivity and competitiveness.In 2011 London set itself the challenge in its Climate Change and Energy Strategy of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by retrofitting 2.9 million homes and 11 million square metres of floor space in public buildings, plus 44 million sq m of private sector workplaces by 2025.

Much has been done, but not enough.

Since 2005 almost 1.5 million works have been undertaken to improve the energy performance of homes in London with 350,000 lofts insulated and 257,000 cavity walls insulated and 803,000 efficient boilers installed. Some of this has been under the Greater London Authority’s RE:NEW programme, which has been operating since 2009.

There are still 650,000 cavity walls that are unfilled and 674,000 lofts that could be made cosier.

Barriers to retrofit

There are many barriers to this further work. Amongst these, Sadhbh Ní Hógáin, housing retrofit project manager at Haringey Council, cites:- the ambiguity of whether you need planning permission for external wall insulation

- inconsistent energy policy from government

- communicating the benefits of solid wall insulation and energy efficiency especially in the private rented sector

- ensuring high standards of installation quality

- the challenge of delivering carbon saving projects during a period of financial austerity.

The state of London’s building stock is becoming an issue for its new mayor, as the 2011 Climate Change and Energy Strategy requires Sadiq Khan to ensure retrofits are carried out on around two-thirds of London’s current non-domestic buildings over the next decade.

Nevertheless the ACE report claims London is falling well behind on its milestones to 2025 and says that the mayor also has his own targets to deliver – when he was elected this year his manifesto promised to make the capital zero carbon by 2050.

“The mayor has set ambitious climate change and energy targets,” Mr Guertler said. “But we are falling well behind on our milestones to reach them. We are improving homes at half the speed we need to – and public sector buildings aside, nobody at City Hall knows what progress is being made to improve our workplaces.”

There has been some success in the hospital sector. Global Action Plan runs an award-winning behaviour change program called Operation TLC, which helps staff take action to improve conditions in buildings used for healthcare. It has been implemented in six NHS trusts across the UK, half of which were in London, and works by harnessing the positive efforts of staff to give patients the best possible care. So far it has succeeded in reducing NHS electricity bills by over £500,000 a year, out of a total bill of £70 million across the UK.

Also, London’s RE:FIT programme has underpinned £93 million in improving public sector buildings. But besides this, there is little policy in place to address the energy efficiency of non-residential properties.

The policy gap

Legislation is coming into force designed to improve the energy efficiency standards in privately rented buildings. This legislation, called Minimum energy efficiency standards (MEES), will make it unlawful for landlords to grant a new lease for properties that have an EPC rating below E from 1 April 2018.Apart from this, at present the UK has little in the way of a national policy in place to promote energy efficiency. With the failure of the Green Deal, action to tackle fuel poverty has fallen dramatically since 2012, as this graph shows:

|

| Action to address fuel policy has decreased dramatically. |

ACE itself has been campaigning for energy efficiency in buildings for decades. It is now asking the new government for seven key policies to be enacted:

- A new energy policy framework

- Buildings energy efficiency as infrastructure

- A leadership role for the public sector

- Zero carbon new builds

- Minimum energy efficiency standards for existing buildings

- Incentives for energy efficiency retrofits

- Improved access to finance for energy efficiency investments

Furthermore, now that the Department of Energy and Climate Change, which instigated the consultation, has been abolished by the new prime minister Theresa May, it is unclear who will even be responsible for driving this policy forward.

For London, at least, Sadiq Khan will have to go it alone.

David Thorpe is the author of:

- Best Practices and Case Studies for Industrial Energy Efficiency Improvement (with Oung, K. and Fawkes, S. UNEP, 2016)

- A London Conversation: Business Briefing on Green Bonds (The Fifth Estate, 2015)

- The One Planet Life (Introduction: Jane Davidson. Routledge, 2015)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Energy Management in Buildings (Earthscan, 2013)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Energy Management in Industry (Earthscan, 2013)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Solar Technology (Earthscan, 2011)

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Sustainable Home Refurbishment (Earthscan, 2010)

Buildings should be at least zero carbon on balance, when totalling the impacts of materials, construction, use and demolition. Features of this are to:

Buildings should be at least zero carbon on balance, when totalling the impacts of materials, construction, use and demolition. Features of this are to: