54% of the world’s population were living in urban areas in 2016. That is predicted to rise to 66% by 2050 according to the United Nations (UN). How will we feed them sustainably? A couple of recent reports offer some valuable pointers, but in this complicated topic, have they missed something?

How to feed ourselves properly is one of the biggest questions facing the human race. Food provision can either worsen or improve climate change, biodiversity, health and soil quality. Poor food provision can lead at its worse to wars, to refugee crises, to mass starvation.

We are feeding ourselves without regard to the biosphere that nurtures and protects us. This is partly why we are in the middle of the

sixth greatest species extinction in the history of the planet.

To an extent, the mess we're in is because we have mostly left food provision to the private sector. This is primarily interested in short term profit and does not factor in the external costs of their activities on their balance sheets. These costs include pollution, soil loss, climate change, diet-related health crises.

Governments at all levels need to implement policies to correct this tendency.

A new report,

What Makes Urban Food Policy Happen? looks at these issues and contains insights from case studies. It is a substantial effort from

The International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems, and examines ways in which cities can design and maintain highly-developed, integrated food-related policies.

But first, more about the context:

The general picture

Ten facts show how much there is to do:

- Global population (currently 7.5 billion) is scheduled to peak at 11.2 billion by 2100 (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2017).

- As many as 795 million people were still food insecure in 2015 (FAO et al., 2015).

- Two billion suffer from the ‘hidden hunger’ of micronutrient deficiencies.

- Over 1.9 billion adults are obese or overweight (IFPRI, 2016).

- One third of agricultural land is degraded (Status of the World’s Soil Resources, 2017)

- More than enough food is produced for today’s global population ( The Global Food System: an Analysis, 2016) but much is wasted and doesn't get to everyone.

- Of the nine 'planetary boundaries' assessed by WWF in its 2016 Living Planet Report four of these global processes have passed beyond their safe boundaries (climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows and land-system change).

- Humanity currently needs the regenerative capacity of 1.6 Earths to provide the goods and services we use each year (WWF).

- The per capita Ecological Footprint of high-income nations dwarfs that of low- and middle-income countries (Global Footprint Network, (GFN) 2016).

- 1.7gha is the available per capita share of ecological biocapacity now - this will decrease with a rising population (GFN). (That means that, if we all had the same equal share of land to support ourselves it would be just 1,700,000 square kilometres each. It sounds a lot, but not when you include all the other species on the planet.)

|

| Global Ecological Footprint by component vs Earth’s biocapacity, 1961-2012. Carbon is the dominant component, and the largest component at the global level for 145 of the 233 countries and territories tracked in 2012, mainly due to the burning of fossil fuels. The green line represents the Earth’s capacity to produce resources and ecological services (i.e., the biocapacity). It has been rising slightly, mainly due to increased productivities in agriculture (Global Footprint Network, 2016). Data are given in global hectares ( gha). |

|

The relative ecological footprints of different countries. High income countries have a much higher footprint. WWF's report says: "Consumption patterns in high-income countries result in disproportional demands on Earth’s renewable resources, often at the expense of people and nature elsewhere in the world." |

As more people become wealthier and live in cities, they will expect their consumption patterns to rise. If we have to feed more people, and reduce our consumption of the Earth's resources to within planetary boundaries, what can we do?

WWF's report says: "root causes include the poverty trap, concentration of power, and lock-ins to trade, agricultural research and technology." To these I would add: ignorance of the sustainable alternatives.

Concentration of power and lock-ins to trade

Much of the problem has been

analysed by the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD).

Their analysis argues that to increase food security we need "policies and programs to diversify diets and improve micronutrient intake; and developing and deploying existing and new technologies for the production, processing, preservation, and distribution of food".

WWF's Living Planet Report agrees, adding that we need a change of mindset – to adjust our 'systems thinking'. "For instance, individual consumers can change their purchasing behaviour, or people with greater political or economic influence can formulate strategies for policy change."

Four certainties arise from this. We need:

- More locally produced and varied diets;

- To generate less food waste;

- To take care of our soils;

- To eat less intensively-reared meat.

Why? Well, just a handful of

mega-companies dominate global food production. In food trading there are only four agricultural firms: ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Louis-Dreyfus, who exert huge influence.

They affect biodiversity through massive land-use intensification and land conversion – habitat loss, and, with just a few crops, a dramatic loss of genetic diversity.

As a result, 75% of the world’s food is generated from only 12 plants and five animal species (

FAO, 2004). Large-scale monoculture operations mean high volumes of chemical inputs equating to pollution, carbon emissions and soil degradation.

Grassland (23% of the Earth's surface) is ideal to retain as grazing for ruminants (since this system of farming supports the soil and sequesters carbon).

But indoor, intensive rearing of animals has the opposite effect. This is mostly because they need feed (soya and grain). A staggering third of agricultural cropland is used to grow this animal feed. The ecological footprint is huge, especially when rainforests are cleared to provide this food.

Eating less of this type of meat would have multiple benefits: on animal welfare, the land, transport impacts, greenhouse gas emissions and human health.

Systemic patterns in the food system – agricultural subsidies, trade agreements, commodity markets – need to alter to effect this change, as do mental habits – such as the belief that higher economic status means higher levels of consumption, especially of meat.

Feeding cities

Cities used to feed themselves from their hinterlands – which were nearby. Now food can come from anywhere in the world. Mapping the ecological footprint of food consumed in cities nowadays would be a huge and complex task.

Then there's the problem of equity. Good, nutritious food may enter a city but does not necessarily reach everyone. Many urban neighbourhoods are poorly served by markets and stores selling healthy, cheap foods, contributing to high incidences of obesity and diet-related ill-health in those areas.

The

‘New Urban Agenda’, adopted by the UN Habitat III conference in October 2016 (Quito, Ecuador) to guide the urbanization process over the next 20 years, makes commitments to improving food security and nutrition, strengthening food systems planning, working across urban-rural divides and coordinating food policies with energy, water, health, transport and waste.

Also, the

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted in 2015 (United Nations, 2015) include one to ‘make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ and many of them address food in one way or another.

In response, a growing number of city governments are developing urban food policies.

Ten examples of urban food policies

Feeding our cities in a way that regenerates the planet's ecology is one of the biggest challenges facing humanity. Many cities are developing policies to tackle this issue, while others have not even begun to consider it.

|

| Empress Green, Staten Island, New York. |

Cities have limited (and variable) powers and responsibilities to deal with food issues within their boundaries. Some of the issues are dealt with at national level, others not at all.

To generate a policy to tackle these issues typically requires different government departments and policy areas to talk to each other and new bodies to be established.

|

| Urban growing in the town of Colomb, near Paris, France. |

Most policies have targeted actions with specific goals – such as addressing health or food waste. These can later be incorporated into more general, integrated food policies, as understanding of the issues increases amongst participants.

The policies form just one part of the broader scale food systems change that is ongoing. This consists of overlapping policies at local, national, regional and global level.

Types of policy

Hundreds of cities around the world have food policies or governance structures. They are often focussed on specific food-related issues such as:

- Lack of access to nutritious food (for example the Public Policy on Food Security, Food Sovereignty and Nutrition in Medellin, Colombia, which includes improving agricultural production in the city districts);

- Obesity (for example the Healthy Diné Nation Act, Navajo Nation, US – a tax on junk food);

- Climate change and waste (for example protection of the “greenways” in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Fasso, and the zero waste policy in San Francisco, US)

- Reviving the local economy and providing jobs, especially for women (for example urban agriculture policy in Cape Town, South Africa; and the Central Market programme in Valsui, Romania)

- Leveraging existing policy responsibilities (for example public food procurement) to achieve new ends

- Rethinking urban planning systems to achieve multiple win-wins (for example the Policy for Sustainable Development and Food in Malmö, Sweden)

- Or a whole a range of different urban challenges (for example the Toronto Food Strategy, Canada).

Ten examples of urban food policies

- 140 signatory cities (as of April 2017) of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, launched in late 2015, have committed to working towards “sustainable food systems that are inclusive, resilient, safe and diverse” — and to encouraging others to do the same.

- The concept of City Region Food Systems has taken off, which involves a "network of actors, processes and relationships to do with food production, processing, marketing, and consumption” across a regional landscape comprising urban, peri-urban and rural areas. This is particularly exciting because it aims to maximize ecological and socio-economic links and co-governance by both urban and regional players:

|

| City Region Food Systems concept diagram |

- The UN Committee on World Food Security is preparing policy recommendations on “Urbanization and rural transformation: implications for food security and nutrition”, to be put forward later this year.

- The C40 Food Systems Network is a workstream of C40. In cooperation with the EAT Initiative, it supports the efforts of 80 global cities to develop and implement measures to reduce carbon emissions and increase resilience in food systems.

- EUROCITIES’ food working group is a “creative hub” for sharing information, ideas and best practice on urban food between members of the network of elected local governments in 130 European cities. Its new report will be out next month.

- The UK Sustainable Food Cities Network has 48 member cities that are developing cross-sector partnerships to promote healthy and sustainable food. Its Policy 1.2.1 calls for "the establishment of statutory Food Partnerships in each regional, metropolitan and local authority in England built on broad civil society and cross-sector participation":

- The Association des Régions de France signed the Rennes Declaration for Territorial Food Systems in July 2014, through which they committed to promoting agriculture and food policies for territorial development, economic development, and sustainable use of natural resources.

- In the Netherlands, 12 cities, one province and three ministries signed the CityDeal “Food on the Urban Agenda“ in early 2017. Not only will the cities and province include food in their own plans and strategies, but they are also collaborating to build an integrated food strategy for the whole country.

- Dame Ellen MacArthur – who sailed single-handedly round the world – calls cities “great aggregators” of resources and materials – especially nutrients from food. The opportunities to collect and reuse these is described in her Foundation's latest publication, URBAN BIOCYCLES, which "highlights the opportunities to capture value, in the form of the energy, nutrients and materials embedded in the significant volume of organic waste flowing through cities, through the application of circular economy principles":

- Gunhild Stordalen, from the EAT Forum in Sweden, believes food is the main issue around which coalesces all the others: climate change, poor health, social inequality, soil loss, biodiversity loss. "Food is the biggest driver of climate change. There is no scientific consensus on solving these interconnected problems. We need action to change this and to end the disconnect between consumption and production". Her work encourages collaboration across sectors globally. "We need new business models as much as new practices."

These are all very exciting, but we are only at the beginning. The potential is huge for involving cities' populations in providing their own food, and linking them back to the origin of their food, and so to nature – a connection all too easily lost in urban life.

The issue of feeding cities sustainably is gradually rising up the political agenda.

Six cities leading in urban food policies

There is evidence that we can feed the future Earth's population of 11.5 billion even if 70% of them live in cities, without reducing the Earth to one big intensive farm and increasing climate change. And if we can learn from six existing cities on how they are beginning to tackle this issue, then there's a chance we can actually do it.

The productivity question

If the amount of food produced per hectare at present can be increased then it will be possible to feed more people with less land as the population of the world increases. Big agriculture uses the argument that it alone can do this to justify its continuing grip on food policy and research, and to push for more genetically modified crops and chemical inputs.

But are they right? Firstly, reducing chemical inputs (nitrate and phosphate fertilisers and pesticides) should be an important policy aim. This is because they are produced using fossil fuels, reduce biodiversity, pollute our watercourses, harm health and, year-on-year, deplete soil fertility and soil carbon.

In the nineteenth century Paris fed itself by obtaining 6-7 harvests a year from its surrounding hinterlands. It did this by using thermophilic (heat-generating, from manure) composting in conjunction with a high labour input and what we'd call today agro-ecological methods, according to regenerative cities expert

Herbert Girardet.

|

| Creating Regenerative Cities by Herbert Girardet (left) book cover. |

Of course, Paris would need a lot more land now as it's far bigger, but 6-7 harvests a year? That's more than big agriculture can manage. It turns out there are four strategies to get more from less land and feed more people in cities:

1.

GM crops are acceptable and useful for resisting pests and drought as long as the seeds are 'open source' and do not lock farmers in to using specific products. They are more resilient and do improve productivity.

2.

Vertical farms growing leafy vegetables claim to be able to produce over 12 harvests per year. They're being developed in many paces, such as the CityFARM project of Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab’s City Science Initiative. In New Jersey, New York State,

Aero Farms has built the largest indoor farm so far. It is 130 times more productive per square foot annually than a field farm, uses 95% less water, 40% less fertiliser, and no pesticides. Crops that usually take 30 to 45 days to grow, like the leafy gourmet greens that make up most of the output, take as little as 12. With aquaponics and hydroponics, potatoes, root vegetables, and fish such as tilapia can be provided.

|

| Aero Farms' indoor farm in New Jersey. There is a synergy between fish and vegetable growing involving aquaculture and hydroponics. |

3.

Agro-ecological smallholdings are more productive than farms.

Data from a conversion of a Welsh sheep farm to this type of horticulture has shown a 30-fold increase in productivity, without subsidy. In addition they improve biodiversity and soil fertility year-on-year through composting and employ more people to keep a closer eye on each square metre of land. Animals (dairy, fowl, pigs) are used productively as part of the growing cycle.

In cities, growing areas using these methods should be encouraged through

education. Such mini-farms can be extremely small and so fit in well within and around urban areas. Ribbon developments an draw their sustenance from the land either side. Growing can also be done on rooftops and back yards (also tackling urban air quality and over-heating). 'Patchwork farm' arrangements such as

Farmdrop in London are springing up whereby multiple producers use mobile technology to coordinate direct sales to customers of organic produce.

|

| The Marta farm, 20 km outside Havana. Cuba is leading the world in regenerative urban farming. |

4.

Diet change. We will have to get used to the idea that to feed half as many more people, we need to adjust our diets and eat less meat and grain. As mentioned in the first article, grassland grazing should be kept to provide meat, but intensive indoor livestock farming reduced because of their respective positive and negative effects on soil quality and climate change. This leaves the production of grains and large-scale pulses like soya. These will have to continue to be grown in fields for bread and other products, but in a more regenerative way, more and more organically using natural pest control techniques.

Cities to learn from

The IPES report,

What Makes Urban Food Policy Happen?, contains five case studies: Belo Horizonte, Nairobi’s Urban Agriculture Promotion and Regulation Act, The Amsterdam Healthy Weight Program, Golden Horseshoe Food and Farming Action Plan and Detroit’s Urban Agriculture Ordinance. Shanghai provides an additional example as it is forging ahead with vertical farming.

The following are only summaries. Much more detail on how the projects came about, the problems they faced and what we can learn from them to replicate elsewhere, is contained in the IPES study.

Belo Horizonte

|

| Belo Horizonte food market. |

Belo Horizonte is a much-praised pioneer in this area. Its government-led alternative food system runs in parallel to the conventional, market-led system.

Programmes are delivered in partnership with civil society, private companies and municipal departments and reach around 300,000 citizens — 12% of the population — every day.

In 2015 the School Meals programme served 155,000 children in the public school system, while the Popular Restaurants served over 11,000 meals per day.

Food is provided locally, creating jobs and educating children about the link between food and the land. There are 133 school vegetable gardens and 50 community gardens. The Straight from the Country programme supports 20 family farmers and 21 grocery stores are in the ABaste-Cer programme.

Amsterdam

|

| Children benefitting from the Amsterdam healthy food programme. |

Amsterdam aims to eradicate overweightness and obesity by 2033.

Unlike obesity programmes in other cities, its policy contains integrated actions across the departments of public health, healthcare, education, sports, youth, poverty, community work, economic affairs, public spaces and physical planning, and organizations from outside local government. It seeks to address the structural causes, including the living and working conditions that make it difficult for people to ensure children eat healthily, sleep enough and exercise adequately. It aims to make the healthy choice the easy choice, and create a healthier urban environment.

The policy was driven by one man: Eric van der Burg of the liberal-conservative People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy. The policy was given no initial budget, in order to show what could be achieved through cooperation and taking joint responsibility.

Golden Horseshoe

|

| Map showing the reach of the Golden Horseshoe Toronto hinterland food supply programme. |

The Golden Horseshoe region runs around the western shores of Canada’s Lake Ontario, including the Greater Toronto area and neighbouring communities. It is densely populated with rapidly expanding cities of educated, affluent professionals.

In 2011/12 seven municipalities adopted a common ten-year plan to help the food and farming sector remain viable. This Golden Horseshoe Food and Farming Plan 2021 has five objectives:

- to grow the food and farming cluster

- to link food, farming and health through consumer education

- to foster innovation to enhance competitiveness and sustainability

- to enable the cluster to be competitive and profitable by aligning policy tools, and

- to cultivate new approaches to supporting food and farming.

Its broad aims and membership have achieved much but also seen conflict arise between advocates of small-scale, ecological agriculture and so-called "big agriculture". Face-to-face meetings are sorting out differences but unfortunately no major food company is represented.

Detroit

|

| Children in Detroit enjoying locally produced food. |

This post-industrial ghost town is reinventing itself using urban farming. In 2012, the Detroit City Plan was updated to feature urban agriculture as a desirable activity, acknowledging the environmental, economic and social benefits.

2013's Detroit Future City Strategic Framework made it a priority for all city stakeholders in order to accelerate economic revival, address land use issues, improve city services, and foster civic engagement. It gave urban agriculture a zoning ordinance, thereby formally permitting, promoting and regulating certain types of food production as a viable land use.

This planning barrier is often a vital issue facing those who want to practice urban farming, especially indoors with “vertical farms”. Entrenched attitudes and vested interests are still being dealt with. This is in the nature of all attempts at “system change”.

But Mayor Mike Duggan has stated a preference for vacant land to be put in the hands of local residents for growing food. Detroit contains several vertical farms, often built in disused warehouses. These grow food organically in controlled conditions, recycling water and nutrients, and using low carbon LED lighting.

Shanghai

Vertical farms exist in an increasing number of cities around the world such as Anchorage, Berlin, Singapore and Tokyo, providing fresh vegetables, mushrooms, herbs and salads, fish, crabs and other foods.

China is leading the world in vertical farming in cities. It's been pioneering the research for many years. Atop the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Beijing, indoor patches of tomatoes, lettuce, celery and bok choy yield between 40 and 100 times more produce than a typical open field of the same size.

Now China is planning a 100-hectare urban farming district in Shanghai, which has a population of 24 million. The

Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District, designed by US-based firm Sasaki Associates, between Shanghai’s main international airport and the city center, will use urban farming as a living laboratory for innovation, interaction, and education. Construction is expected to start in late 2017.

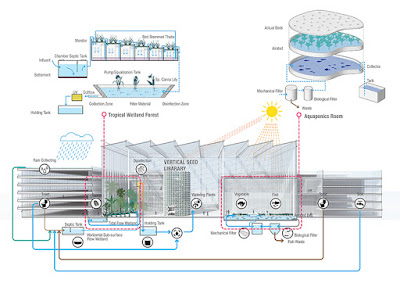

There will be a range of techniques, including algae farms, floating greenhouses, green walls, and vertical seed libraries. An interactive greenhouse, science museum, aquaponics showcase, and market will help to educate children about where their food comes from.

Conclusion

There is no shortage of solutions to the related crises of food, health, climate change and city design. But, from ordinary citizens to government ministers, people need to be more engaged in where their food comes from and what they eat.

Every planner and architect, every health professional, and every educationalist deserves to explore this, for, when it comes down to it, we are what we eat. And what we eat ultimately determines the fate of the planet.

David Thorpe is the author of The One Planet Life, a Blueprint for Low Impact Living.