|

| Julie Hirigoyen, chief executive of the UK Green Building Council. |

The built environment sector places a strong focus on reducing operational carbon emissions in buildings, however embodied emissions often fall by the wayside, despite often accounting for a large proportion of overall emission. New guidance from the UK Green Building Council seeks to fix this by helping clients of built environment projects to commission embodied carbon measurements.

There is already much guidance on measuring the embodied carbon of buildings, but the unique feature of this new guidance is its focus on the contractual demands clients can place on their supply chains.

It begins by outlining the basics of embodied carbon and goes on to give an overview of possible approaches with examples of clauses that could be included in supply chain contracts and practical tips on how to use the outcomes of the resulting assessments.

Launching the guidance at Ecobuild, the UK’s annual exhibition and festival of ecological building, Julie Hirigoyen, chief executive of the UK Green Building Council, said: “We want to see the built environment fully decarbonised and this has to include both embodied and operational carbon. So we continue to advocate for embodied carbon to become a mainstream issue in building design, construction and maintenance.

“As such, we are encouraging our client members and other clients in the industry to create their own embodied carbon briefs by making effective use of this guidance.

“Also, we are working with cities and other local and national authorities to encourage the assessment of embodied carbon within the public sector planning and procurement process.”

David Picton, from multinational facilities management and construction services company Carillion, is one of the supporters of and contributors to the guidance.

“Measuring, tackling and reducing embodied carbon is the hidden prize in shaping a better built environment,” he said.

“We are hoping that this guidance will drive clients, designers, contractors and suppliers to work side by side to develop and maintain infrastructure with the lowest possible carbon content.”

The document will be useful for any financial investors whether in the building of new structures, or the refurbishment of existing ones, and can apply to any type of built structure.

It is not a methodology or standard for the measuring of embodied carbon. Instead it sets out a framework within which such measurements can be gathered and acted upon.

Why do it?

Globally, buildings account for 32 per cent of energy use and 30 per cent of energy-based greenhouse gas emissions. To contribute to the goal of limiting global temperature increase to 2°C the sector must reduce its emissions by a total of 84 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide by 2050.Since the Paris Agreement 91 countries have included some kind of commitment relating to buildings in their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions – their declarations of their commitments to meeting the terms of the Agreement.

There is a strong economic case for considering embodied carbon. For example, buildings have a relatively low cost when compared to many operational carbon saving solutions.

Action to reduce embodied carbon in the building process encourages more efficient “lean build” and resource efficiency, thereby lowering costs. It also unlocks innovation and can be a helpful way for clients to compare the pros and cons of assets. It also achieves credits in some building assessment sustainability rating schemes.

|

| Chart showing the relative embodied and operational carbon of present and projected future buildings. |

What is it?

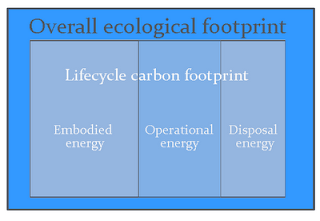

A structure’s embodied carbon is the total greenhouse gas emissions associated with its production.International standards have been developed to help companies manage their carbon footprints, such as PAS 2080:2016 Carbon management in infrastructure.

The embodied carbon impact of building assets is more significant than has been previously thought. Recent research has uncovered that over a 30 year period these emissions typically account for over 50 per cent of the total carbon emitted for some kinds of buildings.

|

| Charts showing the relative carbon costs of different building types. |

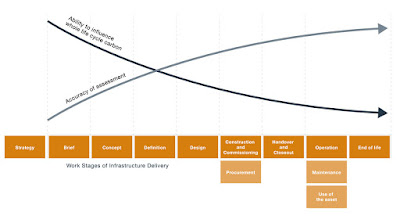

Julie Hirigoyen says that as buildings themselves become better insulated and more airtight, thereby reducing the carbon emissions associated with their use, the proportion of the total carbon emissions that are associated with the production of the elements increases.

It is important to remember that all assessments of embodied carbon are only estimates unless they are based on data specifically relating to the constituent parts as used up to the point of the handover of the building to the client.

They are only as certain as the quality of the data available at the time of assessment, and may be based on standardised assumptions about the life cycle of assets, such as maintenance regimes.

It’s also important to decide when the measurements are to start, what the boundaries are, and whether you are comparing like with like.

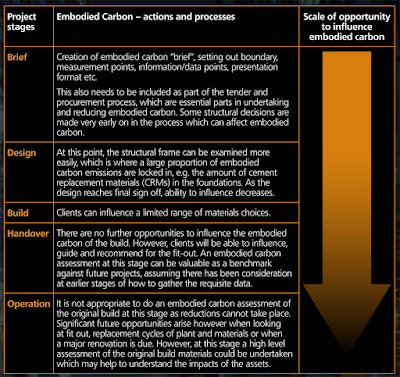

When should the process start?

|

| Chart showing the process of producing a 'carbon brief'. |

Achieving embodied carbon emissions reduction has the greatest impact if considered at the early stages of the construction project when the design and choices of materials can be influenced.

The two major wins for improvement arise from retaining and re-using elements of an asset – in other words minimising the introduction of new carbon emissions associated with production.

For example is possible to examine and improve the proposed mixes of concrete to incorporate higher levels of cement replacement or recycled aggregate.

The guidance lists various datasets and tools that could be used as well as targets that might be adopted, and goes on to describe how the assessments could be benchmarked.

British Land, which is one of the largest property development and investment companies in the UK, is already adopting the above approach. It expects embodied carbon emissions to be measured and reduced for all developments it undertakes costing over £50 million (AU$80.7m).

The company has an aim to reduce the measured emissions from product stage and construction of “landlord” elements by 15 per cent. Each review that it conducts has a champion, usually the structural engineer, and he or she will conduct the review with reference to British Standard EN 15978.

This divides the product stage into three elements – raw material supply, transportation and manufacturing process. The reduction in carbon emissions must be demonstrated through clear assessment and detailing.

Civil engineering company Walsh Construction has also been adopting this approach. It has found that involving clients in reducing embodied emissions from their projects helps carbon savings to “rise considerably”.

“Walsh have shown that it is possible to achieve over 60 per cent savings,” Walsh director Peyrouz Modarres said at Ecobuild.

“Such significant savings of embodied carbon clearly demonstrate the importance of close client engagement as a vital contribution to reducing embodied carbon.”

- See the guidance.

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Sustainable Home Refurbishment

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Energy Management in Buildings

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Energy Management in Industry

- Earthscan Expert Guide to Solar Technology

- The One Planet Life

- Best Practices and Case Studies for Industrial Energy Efficiency Improvement (with Oung, K. and Fawkes, S., UNEP)

Visit his website here.