“While the energy intensity of the buildings sector has improved it is not enough to offset rising energy demand,” International Energy Agency executive director Fatih Birol said at the launch of the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction’s Global Status Report 2017 this week.

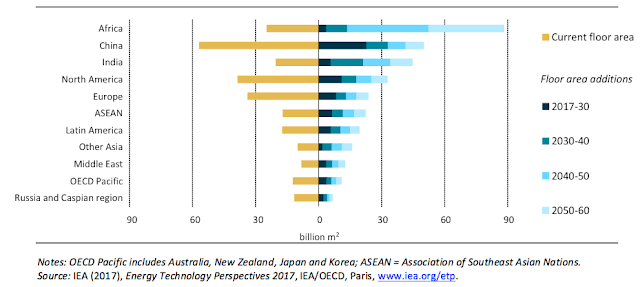

The floor area of buildings worldwide was 235 billion square metres in 2016. By 2060 a staggering further 230 billion square metres will be added – roughly the floor area of all of Japan’s buildings each year.

|

| Global floor area additions by 2016 by key regions |

The report said the urgent task was making these buildings energy efficient to stop them leaking cash and carbon for decades.

“The building sector is seeing some progress in cutting its emissions, but it is too little, too slowly,” UN Environment head Erik Solheim said.

“Realising the potential of the buildings and construction sector needs all hands on deck – in particular to address rapid growth in inefficient and carbon-intensive building investments.”

The increase in demand is caused by population growth but also greater demand per capita for floorspace and a greater demand for energy services.

|

| Erik Solheim |

|

|

“Over the next 40 years, the world is expected to build 230 billion square metres in new construction – adding the equivalent of Paris to the planet every single week,” Dr Birol said. “This rapid growth is not without consequences.”

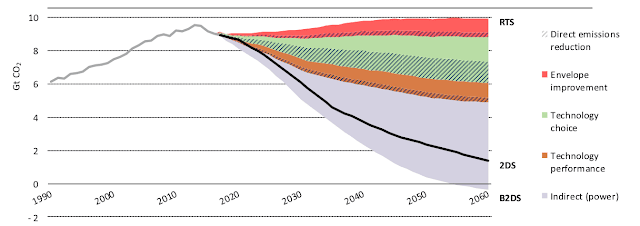

Pledges by individual countries to meet the ambitions of the Paris climate change agreement are still not sufficient to meet the 4.9 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) annual emissions reduction that could be achieved if countries were to pursue strategic low-carbon and energy-efficient building technology deployment.

CO2 emissions from buildings and construction rose by almost one per cent a year between 2010 and 2016, with the report saying a dramatic increase in energy intensity was necessary to arrest this.

|

| Energy-carbon intensities for the building sector by country in 2015 |

In addition, the rate of energy renovations for existing buildings also needs to improve from one to two per cent per year to over three per cent a year in the coming decade, particularly in developing countries where around 65 per cent of all of the building stock expected to be around in 2060 has already been built.

What is to be done

The report goes on to demonstrate many opportunities to install energy efficient and low carbon features and buildings, supported by many examples across the globe.Four things are needed to achieve these goals, the report said:

- Ambitious and transparent commitment with policies and market incentives that encourage the construction sector to meet the sustainable development goals

- Much better building energy codes and certification, labelling and incentive programs, everywhere, with rigorous enforcement

- Wide-scale adoption and investment in high-performance, low-carbon, energy-efficient solutions

- A major shift in financing and investments, with a solid business case for investors, information and financing tools that minimise risk and uncertainty

- Urban planning policies for energy efficiency and renewables

- Improve the performance of existing buildings

- Achieve net-zero operating emissions

- Improve energy management of all buildings

- Decarbonise building energy

- Reduce embodied energy and emissions

- Reduce energy demand from appliances

- Upgrade adaptation for climate-change related risks

- Increase awareness with training and capacity building

|

Final energy consumption by scenario and fuel type for the building sector between 2016 and 2060

|

|

| How to reduce emissions in the global buildings sector up to 2060 |

And although LED sales are now massive, in the residential lighting market less efficient technologies still prevail.

Guidance is available for a global strategy for the buildings sector for high-efficiency product deployment and fossil-fuel phase out, in the GABC Global Roadmap.

One of the buildings highlighted as an example for others to follow is the Edge building in Amsterdam, which uses digital technologies to maximise energy efficiency.

The zero energy building was designed to maximise natural light intake as well as solar electricity production. Smart technologies such as intelligent ventilation systems and connected LEDs allow people to interact with the building and for it to respond to real-time data sensors or occupants’ commands. This means that lighting levels, humidity and temperature can be adapted to the preferences of the occupants while at the same time improving building energy performance.

Many other examples are in the report from different climate zones.

The report – prepared by the IEA and published by the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction for UN Environment – can be downloaded from http://bit.ly/2jwEjZ7.

David Thorpe’s two new books are Passive Solar Architecture Pocket Reference and Solar Energy Pocket Reference. He’s also author of Energy Management in Building and Sustainable Home Refurbishment.