A version of this article was published on The Fifth Estate last week.

Eighty-two per cent of the EU’s coal-fired plants are estimated to be be non-compliant, emitting excessive levels of pollutants. The cost of compliance is estimated to be over €15 billion (AU$22.4b) according to the European Climate Foundation. This seemingly sounds the death-knell for the coal industry in Europe. But will it?

European climate policy is succeeding in decoupling GDP from energy use, but enthusiasm for climate action is waning.

Christian Schaible, a member of the working group that helped draft the revised standards, explained that “not all plants will have the will, the financing, or even the access to the equipment needed to reduce pollution levels”.

“Investments in plants that are already essentially on life support in order to meet climate commitments simply doesn’t make sense.”

He said that plants committing to close could “under strict conditions and in exchange for reduced operation, be granted exceptions in the short-term”.

This is a nod partly to Eastern European countries still struggling with and committed to the legacy of inefficient Communist-era power systems.

Fossil fuel subsidies

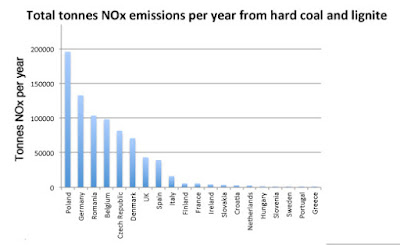

Subsidies for coal continue to abound, as highlighted in a new study, which shows that in Europe, loans of €47.7b (AU$71.1b) have gone to fossil fuel projects since 2013, and many of these projects will continue.The study, from the Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL), also shows that 89.1 per cent of preventable deaths from air pollution in Bulgaria come from fossil fuel pollution.

“Fellow Eastern European countries Romania and Poland could also cut air pollution-based deaths by 71.3 per cent and 51.3 per cent, respectively,” it says.

The Rise of the Visegrad Factor

The Berlin’s Institute for International Political Economy Cenk Olgun said: “The most vehement opposition to ambitious European climate policies have historically come from the post-Soviet eastern member States,” in particular the Visegrad Group (founded in 1991 by Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia) because the bloc “still struggles with a post-communist economic legacy and conventional power sectors”.Energy prices and domestic fossil fuel consumption are especially important issues in these countries. They are highly dependent on imported gas and oil.

The Visegrad Group has succeeded in obtaining a high number of free emission allowances from the EU:

Hungary currently holds the presidency of this group and its declared objectives for the coming year are to promote energy infrastructure, security (meaning more gas and LNG, both seen as a way of weaning off coal) and competitiveness, striking its own idea of a “balance between economic growth and meeting climate policy goals”, and expressing anxiety about “carbon leakage” and “investment leakage”.

Permitted emissions

These Eastern European countries are being permitted to increase their greenhouse gas emissions up to 2020 under rules announced on 20 July. These permits to increase are proposed in the Effort Sharing Decision limits released by the European Commission.These allocate climate targets to each member state within the overall European target in order to decarbonise the non-Emission Trading Scheme sectors – transport (except aviation and maritime shipping), buildings, agriculture and waste.

The overall European emissions target is a 30 per cent reduction on 2005 levels by 2030. The UK’s share of this will be 37 per cent – equivalent to a 45 per cent reduction on 1990 levels. The UK has a domestically agreed Fifth Carbon Budget, which has passed into law and commits it to cutting emissions by 57 per cent on 1990 levels by 2030 – further than the proposed European limits.

Then there’s Brexit

The effect of the UK leaving the European Union has not yet been translated into the effect on Europe’s climate goals. As the UK’s emissions savings compensate for emissions increases in other nations, there will be a knock-on effect. Other nations will have to improve at a faster rate.But this is not reflected in the above 2030 limits. By 2030 the UK will, on its present path, have been out of the EU for a decade.

This oversight is part of the impression coming out of Europe that its climate policy is in disarray.

We saw this in June with the passing of an ineffectual draft of the revised Energy Efficiency Directive.

In addition, the Energy Performance of Buildings directive – agreed by the national governments and the European Parliament – is not being effectively implemented, according to energy efficiency expert Andrew Warren. He complains in a recent piece that “Article 27 of the Directive requires our government to introduce ‘effective, proportionate and dissuasive penalties’ for non-compliance with the directive. These don’t exist.”

Countries very rarely prosecute building owners for non-compliance. The last study of compliance in 2015 found: “In general, information flows and data collection systems across member states for MEP requirements were not fit for purpose” – amongst many other problems with implementation.

The Energy Union strategy and the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement commits to staying “well” below 2°C, while pursuing efforts to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. Taken with other countries’ pledges the EU’s would lead to global emissions of at least 55 GtCO2-e by 2030. But the absolute maximum level of emissions for staying below 2°C would be 40 GtCO2-e. To close this gap, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has asked all countries to reduce their 2030 emissions by at least another 25 per cent.The currently proposed EU energy efficiency target of 30 per cent is too low to meet the Paris Agreement goals. Looking at energy savings alone, by totalling the amount of savings reported by member states in 2014 and 2015 the total savings target is currently on track to be below zero.

One of the few good signs is in France’s newly published climate action plan. This states that France will push the EU to increase the ambition of its emission reduction targets. Wendel Trio, director of Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe, said this “sends a clear message to the whole EU that the full implementation of the Paris Agreement means much deeper emission cuts”.

There is now only a five per cent chance that the planet can avoid warming by at least 2°C come the end of the century, according to research published in Nature Climate Change.

The recent deadly heatwaves in southern Europe look likely to be just a taste of what is to come unless far more drastic action is taken by the European bloc. It could mean over 150,000 people a year dying from heat by 2100 if nothing is done, said The Lancet Planetary Health journal.

The European Union used to lead the world on climate change action. This is not the time for it to lose its nerve.

David Thorpe is the author of Energy Management in Buildings, Solar Technology and Sustainable Home Refurbishment.