The related extinction and climate crises that are threatening the survival of life on earth can only be solved by reducing our ecological footprint – systematically curbing impacts and repairing nature to a level that sustains us within the planet's means.

“We are facing a

climate catastrophe.” These are not just the words of tree-hugging

Gaia-worshippers. They were said this week by the Legal

& General insurance company, the UK's

largest money manager, which last year blacklisted many companies for

being unsustainable.

"As financial

policymakers and prudential supervisors we cannot ignore the obvious

physical risks before our eyes. Climate change is a global problem,"

they said in a statement.

Mark Carney, the

governor of the Bank of England, and Villeroy de Galhau, the governor

of the Banque de France, said the same in an article

in the UK Guardian newspaper this week, as they

called upon financial institutions everywhere “to raise the bar to

address... climate-related risks and to “green” the financial

system”.

The wave of protests

sweeping around cities across the world – International

Extinction Rebellion – is simply asking for

common sense to prevail in the face of the overwhelming threats

facing the planet.

The plain fact is that all money spent everywhere must now be only spent sustainably: to meet our needs while also rebuilding & repairing our planet.

Not unlike the immediate French and worldwide response to the devastation of Notre Dame Cathedral, we must all, especially our leaders, pledge to take urgent action. Watching this global icon go up in flames has struck the hearts and souls of people around the world; within a few days almost €1 billion have been pledged to rebuild it.

Rebecca Johnson, a

former Greenham Common anti-nuclear protestor

compared this to the extinction crisis on BBC News:

"Imagine millions of Notre Dames, all over the world, and not

just art and history, but full of people, animals, plants and

insects, the biodiversity. That is what the protesters are concerned

that leaders are doing nothing about."

The movement's

articulate young visionary, Greta Thunberg, told

an assembly of European members of parliament this week:

"We need cathedral-like thinking".

Watch this speech. She

cries as she laments the rate of extinction of species. "Forget

Brexit, tackle climate change," she tells the MEPs, to a

standing ovation. “Our house is falling apart and our leaders need

to start acting accordingly and they are not.”

As she was speaking,

and all this week, the streets of European cities are being blocked

by Extinction Rebellion protesters, who have pledged not to stop

blocking traffic until their demands are met.

Some city leaders are already responding.

About 100 cities and towns in the UK have already passed resolutions declaring a climate emergency.

The website

climatemobilisation.org

is attempting to keep track of all cities in Switzerland, North

America, Australia and the UK which have done so and has so far

logged about 460 of them, including 18 in Australia, such as Darebin,

Yarra, Vincent, Victoria, Gawler, Mariby, Hawkesbury and Adelaide

Hills.

In California, Los

Angeles, Berkeley, Richmond, Oakland and Santa Cruz have also done

this, to name but a few.

The question for everybody, is what does a council do to follow up, having passed the resolution?

To meet the demands of the resolution they have to become carbon neutral by 2030 at the latest. They also have to include the population in their decision-making.

This will necessitate

action on many fronts.

There is a solution.

All towns, regions and cities must become 'one planet'.

A campaign is beginning to persuade cities, towns and communities to declare “one planet" status that allows them to plan and track a path into the “safe and just space” defined by the work of Kate Raworth and others, where the basic needs of citizens are met without damaging the planet.

The

framework proposed is a way for any town and

city to work out how to #MoveTheDate

of their Earth

Overshoot Day (a measure of unsustainability)

to become more and more sustainable over time using a framework

like this.

I am beginning in my

own part of the world with #OnePlanetSwansea, #OnePlanetCarmarthen

and #OnePlanetLlandeilo. Work is underway to tackle Cardiff, the

capital of Wales.

You can start this

process in your own town, wherever you live.

The aim is to make all

cities regenerative, based on circular economies and renewable

energy, to ensure we live within our means. The solutions already

exist. Policies to support them must be based on evidence, not upon

ideology, belief systems or loyalties, because we are all in this

together.

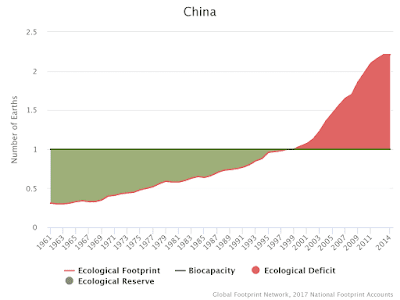

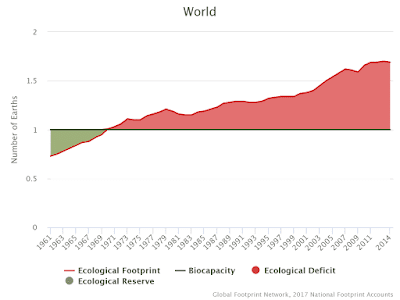

Policymaking has not

caught up with the fact that humanity crossed the threshold of “one

planet” living and began living in deficit way back at the

beginning of the 1970s. This is why we need data, indicators and a

coherent plan to relate our activities to what the biosphere of our

planet can tolerate.

The six-step path towards One Planet Cities and communities

- Obtain community buy-in and feedback at all levels

Hold a series of public meetings and online and

off-line consultations to explain the context and aims in order to

obtain feedback and community buy-in.

- Decide which standards and objectives to use

These will include a methodology and accounting

system and be applicable to all sectors such as soils, biodiversity,

water, energy, buildings, transport, well-being, etc. They must

include ecological footprinting.

- Set baseline – the current situation

Use data and surveys to ascertain the starting

point from which goals will be set: On the supply side, the

productivity of its ecological biocapacity

(greenspace and water bodies). On the demand side, the ecological

footprint – assets/resources required to

produce the natural resources and services it consumes.

- Set targets for each sector over realistic timescales

A system similar to that applied by the UK Climate

Change Act could be adopted, along with the Global Footprint

Network’s Net

Present Value Plus (NPV+) tool to test the

results of different scenarios. A set of five year plans may result,

each with a budget and a set of targets. The overall target could be,

say, 30-40 years away, to meet everybody’s basic needs within

planetary limits. Each short-term target will be a step closer to the

overall one. Each sector (biocapacity, water, food, energy,

buildings, transport, industry, etc.) will have its own schedule.

- Set in place ways to measure them

This should be based on what data is easy and

cost-effective to gather, and relate to the baseline situation,

chosen metrics and sector targets. The data should be transparent and

publicly available. Everybody should be able to view the progress

being made.

- Ratchet down consumption over one or two generations.

Each five-year plan will have its own evaluation

period to check that all expected benefits are resulting, to share

experiences, to accommodate criticisms, to potentially revise plans,

and to celebrate successes.

If a population’s ecological footprint exceeds the region’s biocapacity, that region runs an ecological deficit.

...which almost all regions now do. A region in ecological deficit meets demand by importing, liquidating its own ecological assets (such as overfishing), and/or emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. It must therefore identify the origins, destinations and impacts of consumption.

It would then be

possible to model the effects of changes of policy and practice

towards a circular economy upon the related biocapacity.

Tracking the Human

Development Index (a measure of how human needs

are being satisfied) against the ecological footprint over a time

period can indicate the direction of progress.

Government agencies at

all levels can manage their capital investments in a fiscally

responsible and environmentally sustainable way by using ecological

footprint accounting and the Global Footprint Network’s Net

Present Value Plus (NPV+) tool.

The traditional net

present value (NPV) formula used by economists

adds up revenue and expenditures over a period of time and discounts

those cash flows by the cost of money (an interest rate), revealing

the lifetime value of an investment in present terms.

GFN’s NPV+ tool adds

to this calculation currently unpriced factors, such as the cost of

environmental degradation, and benefits like ecological resiliency.

All costs and benefits – even those where no monetary exchange occurs – thereby can be seen as “cash flows”, and can be evaluated using different future scenarios.

This will provide a more accurate and useful guidance on the long-term value of the investment, because it makes reference to the ecological footprint of the project in question.

The ecological

footprint can therefore help to identify which issues need to be

addressed most urgently to generate political will and guide policy

action. It can improve understanding of the problems, enable

comparisons across regions and raise stakeholder awareness.

By identifying footprint “hot-spots”, policymakers can prioritise policies and actions, often in the context of a broader sustainability policy.

Footprint time trends and projections can be used to monitor the short- and longterm effectiveness of policies.

By understanding where

the best long-term value is, policies can be oriented toward better

outcomes, building wealth, avoiding stranded assets and leaving a

better legacy for future generations.

The standard PAS

2070 can assist with monitoring cities’

carbon footprints of consumption and production. ISO

standards cover environmental management,

energy management and life-cycle analysis to help put in place

procedures for reducing impacts.

At the same time, all

citizens and politicians need to do more to raise awareness about the

issues.

More information at

http://theoneplanetlife.com/

If you want support in

doing this in your neighbourhood, get

in touch.

We can do this. It just

needs a massive, concerted effort.

David

Thorpe is the author of the book

The

'One Planet' Life

and the forthcoming book 'One

Planet' Cities.

All over the world, individuals, groups, towns and cities are struggling with the knowledge that in total, humanity's activities breach the ability of the planet to support them. There is a wide variety of initiatives and programs which are being developed to try to address this and in my

All over the world, individuals, groups, towns and cities are struggling with the knowledge that in total, humanity's activities breach the ability of the planet to support them. There is a wide variety of initiatives and programs which are being developed to try to address this and in my